“She’s from America and she’s married to the same husband, the father of all her children. He doesn’t even drink! And”—my neighbor, unaware that I could understand her Arab dialect, switched to a gossipy whisper—”they even pray and fast!” There were clucks of amazement around the room, and a few pairs of eyes threw astonished glances my way.

She had invited me over to break fast with her. The month of Ramadan, the most important on the Islamic calendar, entailed daily fasting from sun-up till sundown. Ramadan literally means “scorched,” which was very befitting—people were not even allowed to swallow their own spit during the day. Most seemed to love expressing their righteous suffering.

During Ramadan we’d often be invited to break fast with friends, and in that case I’d fast intentionally that day and express to them that I was praying for them and their country during my recent fasting. This was met with great appreciation. The fact that Christians fasted at all was a secret people in our country hadn’t heard before, and they were intrigued. “Are you fasting today?” was the inevitable question many would ask us throughout the day.

“Well, as a follower of Christ I do fast,” I would reply, “but I won’t tell you if I’m fasting today because that’s something between me and God.” They were completely astonished.

We had realized that the labels “American” and “Christian” were practically interchangeable to the people we met—which, by virtue of western media, meant that “Hollywood” and “Christian” were also interchangeable. And this was problematic. Their only unfortunate window into Christianity was what they saw on TV, and needless to say, Britney Spears and reruns of Dallas hadn’t exactly painted a moral picture.

So we needed some new labels. We decided to stop saying, “I’m a Christian” and would say instead, “I’m a follower of Christ.” In the local language, this literally translated as, “I’m a student of Jesus.” We avoided saying we were American when we could—to a large degree, it made sense for us to drop our American identity. This wasn’t easy. We were proud to be American, but holding our American citizenship in equal value to our heavenly citizenship would have limited our witness. God is not American, and he doesn’t advance his kingdom on earth through our Christian American means. In order to reach these people, we needed to contextualize, to learn to appreciate their God-given culture, food, and traditions, to become like them, to see them through God’s eyes. As we fell in love with our new country, especially its people, we understood in a new way why Jesus gave up his Godly form, came down to us in the flesh to meet us on our level, and called us to imitate his example. Fasting with our friends during Ramadan was a simple yet powerful way to do that.

Prayer was another easy way of breaking down misconceptions. Whenever we’d visit people, if they had any issues they were dealing with we’d immediately drop everything and ask if we could pray for them in the name of Jesus. They never refused us and were always thankful.

We found it quite a challenge to do our work projects during Ramadan. Most of the students just didn’t show up, either physically or mentally. Often we’d just have to cancel classes. But the nights were a great time for visiting—people were in such high spirits after the daily fast ended (and ironically, more food was sold and consumed during Ramadan than at any other time of year). We found the late nights a bit of a challenge, but it was nothing a cup of coffee in the morning wouldn’t solve. I’m not sure where Stephen found his boost of energy every morning. It was clearly a God thing. So many times during visits with friends I would sit across the room just watching how Stephen effortlessly showed the love of Christ to these wonderful people, his face aglow as he smiled and conversed with them. They were clearly aware that this “man of God,” as the locals often referred to him, loved them dearly.

Other things within the culture were harder to get used to, though. The rules of public affection, for instance, were totally foreign to our western minds. Not even being able to hold Stephen’s hand when we walked together drove me a little crazy at first. Stephen and I felt compelled to make a point of expressing our love for each other in public as much as we could, without being too physical. We hoped to show a good example of a Christ-like marriage in this divorce-torn society, so we compensated for the lack of physical affection by being extra affectionate verbally and smiling at each other a lot. That was our normal behavior, so it didn’t take much extra effort. But it certainly seemed to strike other people as interesting and different.

We’d realized that if we were going to settle in here and not go crazy in the face of everything that was so different, we needed to maintain a good attitude. The people of this impoverished nation seldom complained. They didn’t have Walmart and online shopping and twenty fast-food menus to choose from—they ate rice and couscous every day of the week. But they never moaned about it. That humbled us. We’d been spoiled back home. The kids would complain sometimes, as kids do, but Stephen and I tried not to nurture it, least of all contribute to it. Attitudes are contagious, and it worked both ways. If we could learn to love the country and cultivate positivity, the kids would catch on.

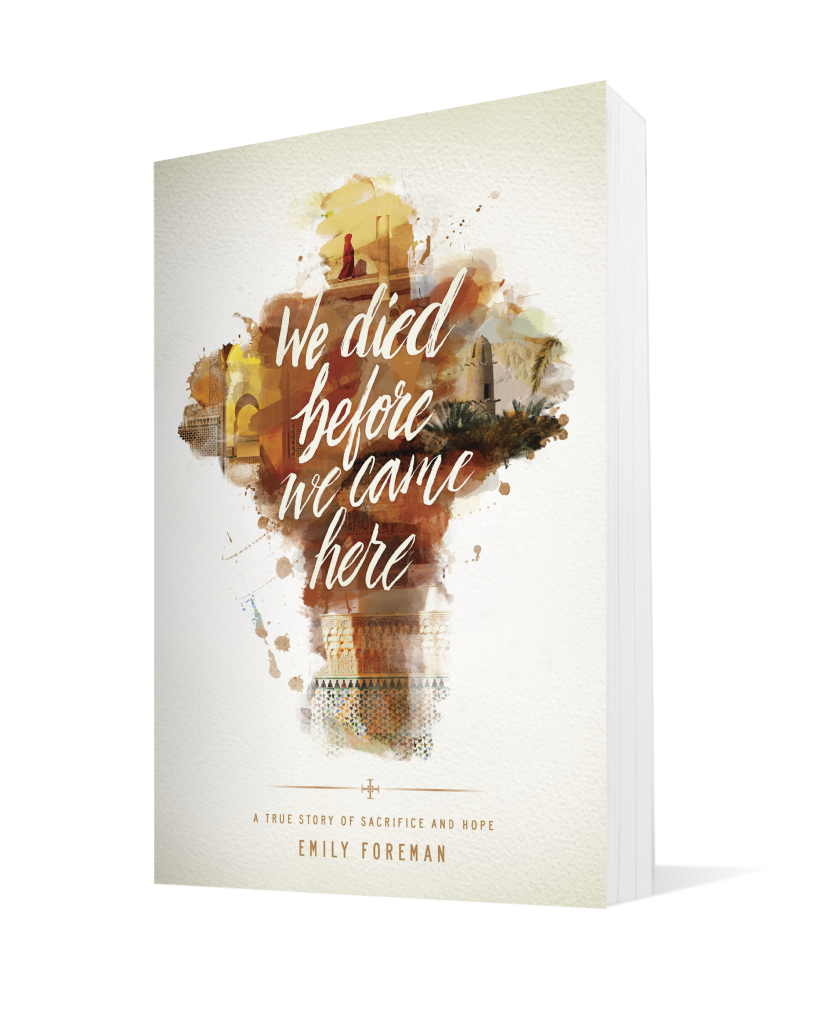

You’ve been reading from We Died Before We Came Here, a gripping account of missionaries in North Africa.

If not you, who? If not now, when? This was the challenge answered by Stephen Foreman and his wife, Emily, when they traded in their American white picket fence for a giant, dusty sandbox as missionaries in the deserts of North Africa. Stephen had given Emily a well-read copy of Foxe’s Book of Martyrs on their first date, a telling foreshadowing of the ultimate cost he would pay. Read chapter one for free.