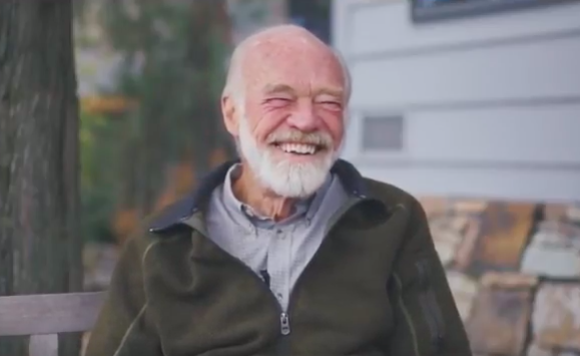

On October 22, 2018, at the age of 85, Eugene Peterson passed from this earth to more fully be with his creator. He is the author of many books and of THE MESSAGE bible translation. He has completed his journey along the sawdust trail and has entered the life to come in “the new country of grace—a new life in a new land!” (Romans 6:1-3, The Message). He is survived by his wife, Jan, his three children, and many grandchildren. In honor of a life well-lived, here is an excerpt from his book Living the Resurrection. To learn more about Eugene and his legacy click here.

The Practice of Resurrection at Every Meal

The Gospel writers are fond of telling stories of Jesus at meals. The meal was one of their favorite settings for showing Jesus as he revealed himself, talked, worked, and welcomed men and women to him.

Formation-by-resurrection does not depend on a specially prepared setting or a carefully selected time and place. The norm is the normal. There is nothing more normal and routine and everyday than eating a meal.

Our common humanity is out in the open as we eat together. We need to eat to stay alive, and at this meal we’re all eating the same thing—vegetables, fruits, breads. The act of eating together has a wonderful way of obscuring—at least temporarily—self-importance.

Christian practice in matters of spiritual formation goes badly astray when it attempts to construct or organize ways of spirituality apart from the ordinariness of life. And there is nothing more ordinary than a meal. Breakfast and supper. Fish and bread. The home in Emmaus and the beach in Galilee. These provide the conditions and materials for formation-by-resurrection.

Both of these meals were what we might call working meals. They weren’t specially prepared for the purposes of a spiritual revelation. They weren’t “staged.” They were a natural and integral part of daily life.

We have wonderful metaphors in our Scriptures that use food as a way of talking about an appetite for God: “O taste and see that the Lord is good” (Psalm 34:8); “Blessed are those who hunger and thirst for righteousness, for they shall be satisfied” (Matthew 5:6); “My soul is feasted as with marrow and fat” (Psalm 63:5); and Jesus’ “I have food to eat of which you do not know” (John 4:32).

But these resurrection meals were not metaphorical. They ate real bread and actual fish. Baked bread, fried fish—food for the stomach.

There is a place for getting away from our daily lives to pray and reflect and rest. Jesus is also a model for doing this: “And in the morning, a great while before day, he rose and went out to a lonely place, and there he prayed” (Mark 1:35). But however much these practices of withdrawal are useful and necessary—very necessary—what Luke and John are both making us face with their stories is that a primary place for spiritual formation, formation-by-resurrection, is the daily meals we sit down to in the course of our daily work.

Every time we pick up a knife and fork, every time we say, “Pass the salt, please,” every time we take a second helping of cauliflower, we are in a setting congenial to spiritual formation.

There is a venerable, but I think wrongheaded, tradition in some parts of the church of using the resurrection for strictly apologetic purposes—using it to prove the divinity of Jesus. There is obviously something to apologetic uses of the resurrection. Paul does it. But even Paul, for the most part, brings up the resurrection of Jesus to engage us in the practice of resurrection.

I’m not using the word practice like in practicing the piano. Practice is a word we say when a doctor has a practice or enters his practice. It’s one of those all-encompassing words that includes everything we’re doing.

A meal is a host/guest arrangement. The meal itself is usually the work of many hands, both apparent and hidden. But a host, whether explicitly or implicitly, sets the terms and conditions of the meal. The best hosts do this most inconspicuously, so it might be difficult at times for an outsider to discern the difference between the host and the guest.

The host/guest reality that is present in all meals taken in common provides extensive experience in the nature of spiritual formation. The guest at a meal is fully participating. The host doesn’t eat the guest’s meal, for example. But at the same time, the guest is totally dependent on the host. As guests, we are at the table in the first place because of an invitation. The food was purchased or grown, prepared, and served by the host—although as guests we may have been invited to help. And the host is going to clean up afterward.

No wonder the meal is such a frequent biblical setting for experiencing the ways of God in our lives. We’re totally involved and at the same time totally not in charge. But these fused totalities can be nearly indiscernible in actual practice. “Host” is not a totalitarian role. At the table of a genial and experienced host, guests experience enormous freedom and spontaneity.

Jesus is host, always. We are never “in charge” of our spiritual formation. We don’t decide the menu. We don’t customize the details according to our tastes and appetites. But at the same time, we are completely present and participatory, engaged in the actual formation-by-resurrection itself.

The Deconstruction of Meals

We find ourselves living in a time when the common meal has been pushed to the sidelines. The machine and its metaphors dominate the way we live and think and talk about the way we live.

The common meal is probably the primary way by which we take care of our physical need for food and our social need for conversation and intimacy and our cultural need to carry on traditions and convey values. The meal—preparation, serving, eating, cleaning up—has always been a microcosm of the intricate realities that combine to make up even the simplest life of men, women, and children. Because it is so inclusive (anyone and everyone can be included in the meal) and because it is so comprehensive (taking in the entire range of our existence—physical, social, cultural), the meal provides an endless supply of metaphors for virtually everything we do as human beings. These metaphors nearly always suggest something deeply personal and communal—giving and receiving, knowing and being known (“taste and see that the Lord is good”), accepting and being accepted, bounty and generosity (“land flowing with milk and honey”).

And always, deeply embedded in the common meal—sometimes it’s invisible, and we don’t see it—is the experience of sacrifice: one life given so that another may live. It may be the life of a carrot or a cucumber or a fish or a duck or a lamb or a heifer, but it’s life. Eating a meal involves us in a complex, sacrificial world of giving and receiving. Life feeds life. We are not self-sufficient. We live by life, and life is given to us.

The prominence of these meals keeps us in intimate touch with our families and our traditions in which we are reared, personally available to friends and guests, morally related to the hungry, and, perhaps most of all, participants in the context and conditions in which Jesus lived his life, using the language he used.

But the centrality of the meal in our lives today is greatly diminished. We still eat, of course, but the world of the meal has disintegrated. The exponential rise of fast-food restaurants means there is little leisure time for conversation. The vast explosion of restaurants means there is far less food preparation that takes place in the home. The invasion of the television set to a place at the head of the table at family meals virtually eliminates personal relationships and conversations. The frequency with which prepared and frozen meals are used erodes the culture of family recipes and common work. All this and more means that the meal is no longer easily accessible or natural as the setting in which to encounter the risen Christ. For most of us, the machine has replaced the meal as the dominant feature and metaphor of daily living.

But we still eat meals—all of us. So the meal remains a major opening, place, condition in which we can practice formation-by-resurrection, though we will probably need to be more deliberate and intentional about it.

The Shape of the Liturgy

The focal practice for the meal and formation-by-resurrection is the Lord’s Supper. We variously designate it Holy Communion, the Lord’s Table, the Holy Eucharist. This practice has, from the beginning of our Christian way, occupied a central place in our worship. There is also a strong and continuous tradition in Christian practice of treating every meal as a kind of mini-sacrament. This tradition has a firm foundation in the biblical language that describes what Jesus did when he gathered people into his presence and ate with them.

Four different times we have a sequence of four verbs to describe what Jesus does at meals. The four verbs are took, blessed, broke, and gave. This is what Dom Gregory Dix calls “the shape of the liturgy.” Early on in the Christian community, worship was defined by this fourfold Eucharistic shape, and it has continued to be the pattern ever since. But more than worship was thus defined. Our very lives “in the land of the living” take on the shape of the meal, this central and dominant resurrection meal.

Jesus takes what we bring to him—our bread, our fish, our wine, our goats, our sheep, our sins, our virtues, our work, our leisure, our strength, our weakness, our hunger, our thirst, whatever we are. At every table we sit down to we bring first of all and most of all ourselves. And Jesus takes it—He takes us.

Jesus blesses and gives thanks for what we bring, who we are in our bringing. He takes it to the Father by the Holy Spirit. Whatever is on the table and is around the table is lifted up in blessing and thanksgiving.

Jesus breaks what we bring to him. The breaking of our pride and self-approval opens us up to new life, to new action. We discover this breaking first in Jesus. Jesus was broken, his blood poured out. And now we discover it in ourselves.

Then Jesus gives back what we bring to him, who we are. This self that we offer to him at the Table, is changed into what God gives. Transformation takes place at the Table as we eat and drink the consecrated body and blood of Jesus. A resurrection meal. “Christ in me.”

We initiate the practice of resurrection at the Eucharistic Table, but it doesn’t end there. We continue the identical practice at every meal we sit down to. For the Christian, every meal derives from and extends the Eucharistic meal into our daily eating and drinking, tables at which the risen Lord is present as host.

All the elements of formation-by-resurrection are present every time we sit down to a meal and invoke Jesus as host. It’s a wonderful thing, really, that one of the most common actions of our lives is also the setting in which the most profound transactions take place. The fusion of natural and supernatural that we witness and engage in the shape of the liturgy continues—or can continue—at your kitchen table.

You’ve been reading from Eugene Peterson’s Living the Resurrection. To learn more about Eugene and his legacy or THE MESSAGE click here.