In this post, taken from the foreword of Refractions: A Journey of Faith, Art, and Culture 15th Anniversary Edition, Tim Keller tells a story of how art turned the hearts of enemies into friends.

The movie Joyeux Noel (2005) is the true story of the famous “Christmas Truce” of 1914. It depicts how, during the hostilities of World War I, the French, Scottish, and German troops spontaneously laid down their weapons, came up out of their trenches, and fraternized during an informal, unauthorized armistice. And at the heart of this astonishing grassroots effort at peacemaking was art.

Kaiser Wilhelm II had sent thousands of Christmas trees to the front lines in order to boost the morale of the German troops. After the trees were set up over their trenches, in sight of the enemies’ lines, a German soldier who was a tenor began to sing the Christmas hymn “Stille Nacht” (Silent Night). Soon the French and Scottish troops began singing along in their own languages. Finally, soldiers climbed out of their trenches without their weapons and began to talk, then exchanged gifts, and finally even engaged in games of soccer. (The full true story is told by Stanley Weintraub in Silent Night: The Story of the World War I Christmas Truce; Plume, 2002.)

The movie adds a fictional character to the true story in the form of a world-class soprano to go with the great tenor. The beauty of their singing breaks through the political dividing walls and unites the opponents in joy and tears. I’ve seen something of this unifying power even in my own church services. Because I minister in New York City, our congregation contains some of the best musicians in the world (literally). The music in our services is always excellent, but occasionally we have a musical offering that is so superb and affecting that everyone listening is stunned into silence and moved to tears. And guess what? It is not members rather than visitors, or Christians rather than non-Christians, who are touched. Everyone is brought together; everyone is included. Interestingly, this only happens when the art is skillful and well done. When the music is mediocre or bad, members may be edified a bit if they know and love the musician personally, but visitors and strangers are bored and excluded by the experience.

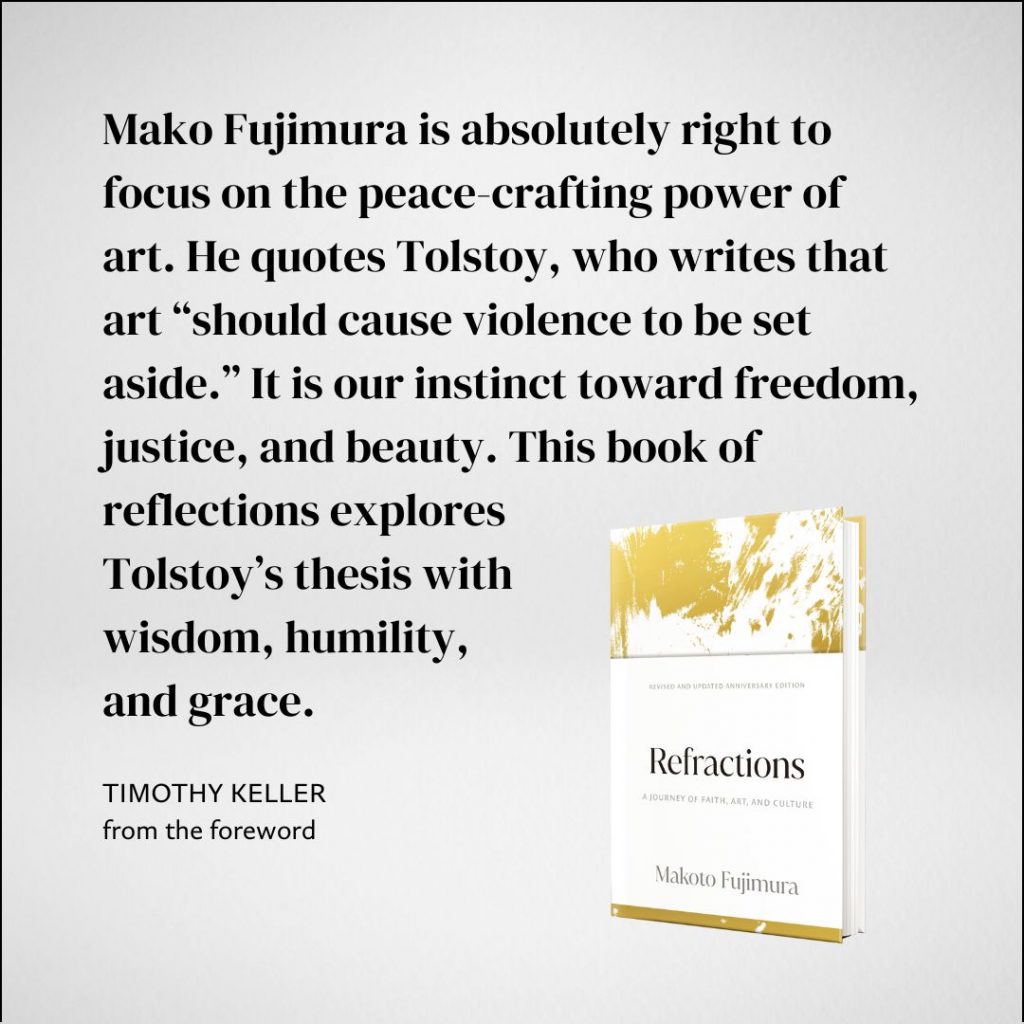

Mako Fujimura is absolutely right to focus on the peace-crafting power of art. He quotes Tolstoy, in his book, What Is Art?, who writes that art “should cause violence to be set aside.” It is our instinct toward freedom, justice, and beauty. This book of reflections explores Tolstoy’s thesis with wisdom, humility, and grace.

I have been a friend and co-minister in New York City with Mako since 1990. Mako’s International Arts Movement (now IAMCultureCare) has been a pioneering effort to integrate thoughtful faith with the creation of art that moves us toward the world “that ought to be.” I’m delighted to see this book, Refractions, appear and honored to be able to recommend it to all.

TIM KELLER

New York City, 2008

What people are saying about Refractions:

MAKOTO FUJIMURA

Makoto Fujimura is a world-renowned artist whose process driven, refractive “slow art” has been described by David Brooks in The New York Times as “a small rebellion against the quickening of time.” Fujimura’s unique fusion of contemplative art and expressionism is credited to his bicultural arts education. He graduated with a Bachelor of Arts degree from Bucknell University, then studied traditional Japanese painting at Tokyo University of the Arts. He is a recipient of 2023 Kuyper Prize for Excellence in Reformed Theology and Public Life.